- left-hemisphere

- right-hemisphere

- There are finite games within infinite ones, but no infinite games inside of finite ones.

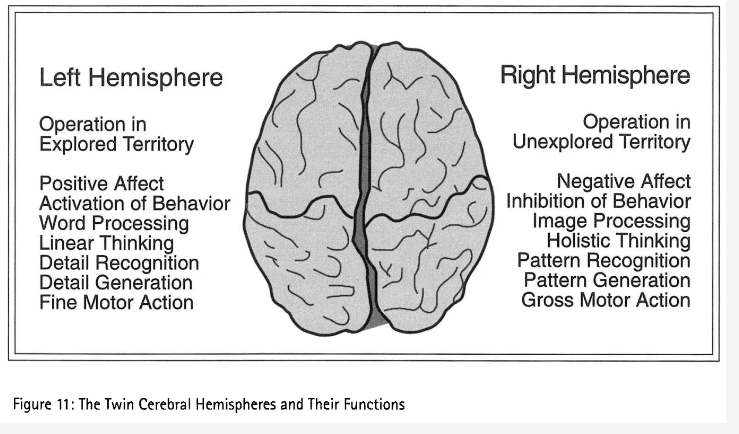

The left hemisphere's job is to create a belief system or model and to fold new experiences into that belief system. If confronted with some new information that doesn't fit the model, it relies on Freudian defense mechanisms to deny, repress or confabulate—anything to preserve the status quo. The right hemisphere's strategy, on the other hand, is to play "Devil's Advocate," to question the status quo and look for global inconsistencies. When the anomalous information reaches a certain threshold, the right hemisphere decides that it is time to force a complete revision of the entire model and start from scratch. The right hemisphere thus forces a "Kuhnian paradigm shift" in response to anomalies, whereas the left hemisphere always tries to cling tenaciously to the way things were.

– (Phantoms in the Brain, pp. 96-98)

Take the following example of a syllogism with a false premise: Major premise: all monkeys climb trees; Minor premise: the porcupine is a monkey; Implied conclusion: the porcupine climbs trees. Well — does it? As Deglin and Kinsbourne demonstrated, each hemisphere has its own way of approaching this question. At the outset of their experiment, when the intact individual is asked "Does the porcupine climb trees?", she replies (using, of course, both hemispheres): "It does not climb, the porcupine runs on the ground; it's prickly, it's not a monkey." [...] During experimental temporary hemisphere inactivations, the left hemisphere _of the very same individual (with the right hemisphere inactivated) replies that the conclusion is true: "the porcupine climbs trees since it is a monkey." When the experimenter asks, "But is the porcupine a monkey?", she replies that she knows it is not. When the syllogism is presented again, however, she is a little nonplussed, but replies in the affirmative, since "That's what is written on the card." When the right hemisphere of the same individual (with the left hemisphere inactivated) is asked if the syllogism is true, she replies: "How can it climb trees — it's not a monkey, it's wrong here!" If the experimenter points out that the conclusion must follow from the premises stated, she replies indignantly: "But the porcupine is not a monkey!" In repeated situations, in subject after subject, when syllogisms with false premises, such as "All trees sink in water; balsa is a tree; balsa wood sinks in water," or "Northern lights are often seen in Africa; Uganda is in Africa; Northern lights are seen in Uganda", are presented, the same pattern emerges. When asked if the conclusion is true, the intact individual displays a common sense reaction: "I agree it seems to suggest so, but I know in fact it's wrong." The right hemisphere dismisses the false premises and deductions as absurd. But the left hemisphere sticks to the false conclusion, replying calmly to the effect that "that's what it says here." In the left-hemisphere situation, it prioritizes the system, regardless of experience: it stays within the system of signs. Truth, for it, is coherence, because for it there is no world beyond, no Other, nothing outside the mind, to correspond with. "That's what it says here." So it corresponds with itself: in other words, it coheres. The right hemisphere prioritises what it learns from experience: the real state of existing things "out there". For the right hemisphere, truth is not mere coherence, but correspondence with something other than itself. Truth, for it, is understood in the sense of being "true" to something, faithfulness to whatever it is that exists apart from ourselves. However, it would be wrong to deduce from this that the right hemisphere just goes with what is familiar, adopting a comfortable conformity with experience to date. After all, one's experience to date might be untrue to reality: then paying attention to logic would be an important way of moving away from from false customary assumption. And I have emphasized that it is the right hemisphere that helps us to get beyond the inauthentically familiar. The design of the above experiment specifically tests what happens when one is forced to choose between two paths to the truth in answering a question: using what one knows from experience or following a syllogism where the premises are blatantly false. The question was not whether the syllogism was structurally correct, but what actually was true. But in a different situation, where one is asked the different question "Is this syllogism structurally correct?", even when the conclusion flies in the face of one's experience, it is the right hemisphere which gets the answer correct, and the left hemisphere which is distracted by the familiarity of what it already thinks it knows, and gets the answer wrong. The common thread here is the role of the right hemisphere as "bullshit detector". In the first case (answering the question "What is true here?") detecting the bullshit involves using common sense. In the second case (answering "Is the logic here correct?"), detecting the bullshit involves resisting the obvious, the usual train of thought.

See

Link

- McGilchrist's brain hemisphere model

- 2019 Yearly Review: Divided Brain Reconciled by Meaningful Sobbing

- Attention is not just receptive, but actively creative of the world we inhabit. How we attend makes all the difference to the world we experience.

- Split Brain Video

- Split brain with one half atheist and one half theist

- Left Brain & Right Brain: 20 Brain Hemisphere Differences from “The Master and His Emissary” (+ Infographic)

- TMAHE(The master and the emmisary book club)

- The Master and His Emissary: Conversation with Dr. Iain McGilchrist

- A Complete Breakdown of Iain McGilchrist's INSANE Ideas about the Brain

- Hemisphere hypothesis